Navigating Tough Conversations

Addressing conflict with confidence

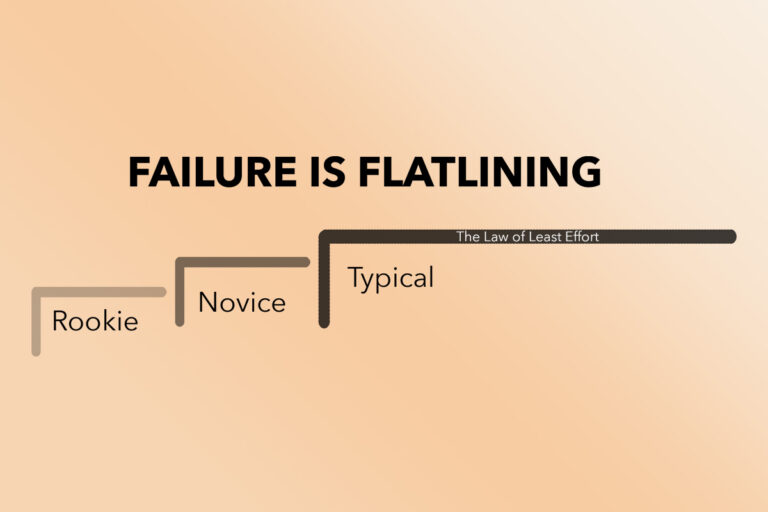

No matter the industry or leader, having hard conversations is never easy. Some leaders procrastinate, others resort to forcing their way through challenges or putting on the appearance of being confident, while feeling like they are just faking it. Even the “tell-it-like-it-is” leaders are concerned about coming across as too bossy.

Whether we are conflict-avoidant or willing to confront issues straight on, it’s important to note that 80% of communication is nonverbal. The people we communicate with will pick up on our anger, resentment or internal discomfort. Most leaders rely on their intellect to navigate conflict. However, this approach will have little impact when dealing with emotional responses in ourselves and others.

Leaders need to develop emotional and physiological intelligence. Physiological intelligence is about expanding our awareness of what is occurring in our nervous systems and bodies, which is typically below the radar of our conscious awareness. When we can work with our nervous system responses, we can have clear and calm accountability conversations that make a difference in the behaviors and actions of others.

Physiological intelligence is about expanding our awareness of what is occurring in our nervous systems and bodies.” Leslie Cunningham

Think about a conversation you’ve been avoiding but know you need to have. Recall what the person said or did that upset you. As you bring the situation back to your mind, you might notice that your breathing becomes shallow. Perhaps you feel constriction in the chest, an increased heart rate or your speech is hurried and rushed. You might be someone who clinches your jaw or holds your fists tightly as your muscles tense, and your skin might feel hot or flushed as your frustration increases.

When our internal tension and frustration rise during a conflict, it can cause an escalating stress response in the people we are communicating with. Engaging in conflict with others is hard and uncomfortable. Naturally, most of us would rather avoid these situations altogether.

For most people, the elevated stress response stems from our past and early childhood upbringing. As children, we developed automatic response strategies to challenging situations because we didn’t have the appropriate tools. We also may have lacked good role modeling from the adults in our lives to show us how to handle conflict in calm, effective ways.

I grew up in a family of four kids in a two-parent household. Even though my mother was very loving, she was quick to react. I was always on alert for when she might get upset. When she did, I would instantly tense up and try whatever I could to quell or get away from her anger. Over time, I became a very avoidant, conflict-adverse person, which formed ineffective habits of rescuing others, people-pleasing and trying to resolve situations hastily just to make the conflict and my discomfort disappear.

Because of our upbringings and experiences, our nervous systems will almost always register conflict and difficult conversations as life-threatening. We feel anxious, our heart rate increases and we can’t think clearly. But these conversations are not life-threatening at all.

The next time you’re in conflict, ask yourself, “Is this situation actually life-threatening and physically dangerous, or am I just experiencing uncomfortable feelings?” Doing this will provide you with a reality check.

This powerful, simple practice has led to profound results for many leaders. It’s how we can build an internal sense of safety, leading to effective, clear and impactful conversations. This is what it means to address conflict through emotional and physiological intelligence.