When most in the industry think of swim spas, they picture the acrylic, portable units that took off in the early 2000s. But alongside that story — sometimes intersecting, sometimes running parallel — is another: the rise of swim machines. These products didn’t look like stretched hot tubs. They weren’t designed for portability. Instead, they were built around propulsion technology, with the goal of creating the best possible swim in the smallest possible space.

It was this focus on how the water moved that not only defined these companies but also helped shape consumer expectations of the entire category.

From boats to pools: SwimEx and the paddlewheel current

In 1986, Everett Pearson, already a legend in the fiberglass boatbuilding world, was introduced to a prototype in Boston. Stan Sharon and Cy Mermelstein — the latter an MIT engineer — had designed a stainless-steel pool that used a massive paddlewheel to generate a smooth, riverlike current. Sharon invited Pearson to “get your swim trunks and come up to Boston.” Pearson tried it, saw the potential and soon after, SwimEx was born.

“We bought the rights to their technology and their patent,” says Suzanne Vaughan, Pearson’s daughter and now president of SwimEx. “We started building them out of fiberglass. The way we build the pool today is the same way we built the boats — only instead of keeping the water out, we now keep the water in.”

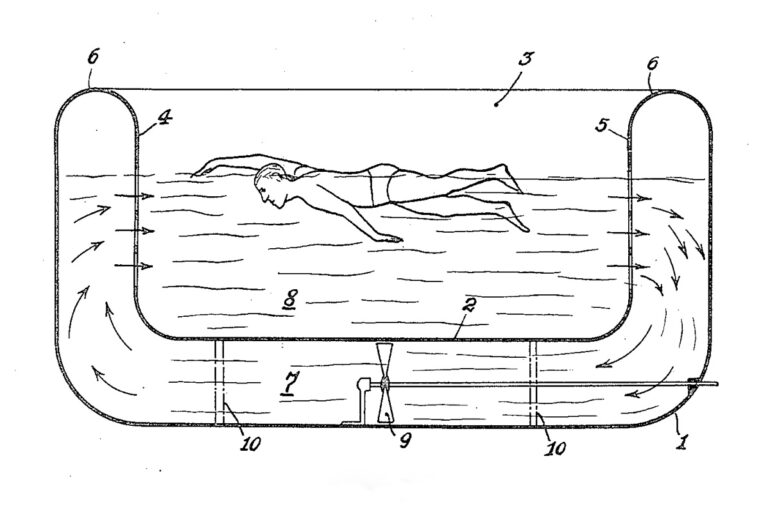

The paddlewheel created what Vaughan still describes as “the most natural swim that you can get in a small space. … It’s literally like being in a river.” The broad, wall-like current wasn’t just for swimming. It made running, walking and rehab exercises possible too. That adaptability pushed SwimEx beyond the backyard. By the early 1990s, the company was working with Ron O’Neill, then the head trainer for the New England Patriots, to design features for athletic and therapy use.

From there, SwimEx became a fixture in training rooms, rehab clinics and high-end homes.

Endless Pools and the power of “swim at home”

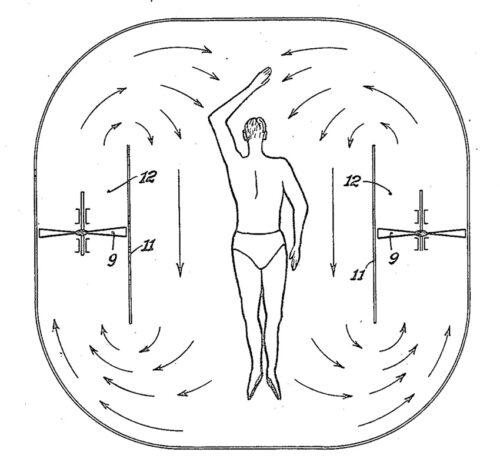

At nearly the same time Pearson was testing that first paddlewheel pool, James Murdock was in New York City, tinkering with his own design. His concept wasn’t fiberglass but a modular steel-panel and liner system paired with a propeller current. The key wasn’t just the engineering — it was the accessibility. Panels and parts could be carried through a doorway and assembled in a basement, garage or backyard.

If SwimEx leaned on relationships with trainers and therapists, Endless Pools made its mark through marketing. In 1989, Murdock placed a tiny black-and-white ad in The New Yorker with the headline “Swim at Home,” generating 300 calls. That initial proof of interest gave Endless Pools both early customers and the confidence to push ahead with direct-to-consumer sales.

Later, an infomercial featuring Olympic champion Rowdy Gaines further cemented the company’s place in the public imagination. “People would say to me, ‘I know Endless Pools from the commercial — oh, and I guess Rowdy Gaines was in it too,’ ” Murdock says. The brand became so widely recognized that “Endless Pool” still functions as shorthand for swim-in-place pools in general.

The Swimcizor: Propellers for the mass market

Another important chapter in the evolution of swim machines came a decade later. Byron Shannon, an inventor working out of Fort Myers, Florida, developed a compact, propeller-driven current generator he called the Swimcizor. Unlike SwimEx’s paddlewheel tanks or Endless Pools’ modular steel-panel kits, Shannon’s unit could be dropped into an existing pool. Suddenly, swimming against a smooth, powerful current wasn’t just for custom-built setups — it could be added to almost any vessel.

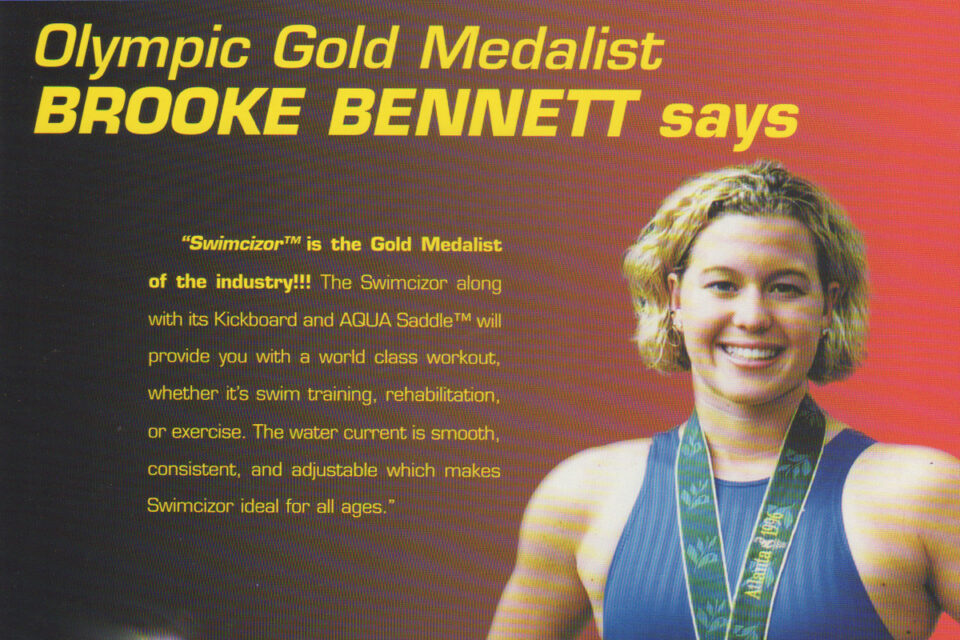

The Swimcizor was eventually sold to Quaker Plastic Corporation, which manufactured and marketed the device. At its peak, the product was showcased at The Pool & Spa Show in Atlantic City, where Quaker built a vinyl-liner pool right on the show floor. Olympic swimmer Brooke Bennett demonstrated the Swimcizor by swimming against its current just inside the main entrance, drawing crowds and headlines.

Despite the fanfare, the Swimcizor never reached its full potential. Quaker Plastic was sold to Cardinal Systems, and the product was discontinued. But its influence lived on. As longtime industry veteran Dave Hazel recalls, “The Swimcizor technology was subsequently incorporated into most of the propeller-driven current generators in use today.” The notable exception, of course, was Endless Pools, whose invention predated Shannon’s design.

Still, the Swimcizor underscored an important truth: Propeller currents offered a vastly better swim than traditional jets. “The propeller drive creates a powerful yet clear current to swim and exercise against,” Hazel says. “The Swimcizor was unique because it allowed a current generator — or swim machine — to be easily and affordably added to almost any spa or pool.”

Now it’s Murdock who is selling a swim machine, the Slipstream, that can be dropped into existing pools. He sold Endless Pools to Watkins Wellness in 2015, but found retirement boring during COVID and returned to the category with the Slipstream.

Parallel tracks, shared impact

Though different in technology, distribution and customer base, SwimEx, Endless Pools and Swimcizor were shaping the same story: that swim-in-place pools were serious exercise machines, not just oversized hot tubs. Vaughan admits Endless was the competitor she heard about most often. “I always tell people, go try both,” she says. “If you’ve got the budget, they usually come to SwimEx. But Endless has done a great job with awareness. They’ve made the whole category more visible.”

Even Murdock concedes the paddlewheel had the edge. “They have the best swim,” he said of SwimEx, “there’s just no way around it.” That mutual respect underscores how the companies, in their own ways, raised the bar.

For SwimEx, it was about being the gold standard for current quality and durability. For Endless, it was about accessibility and marketing sophistication. For Shannon and the Swimcizor, it was about democratizing propeller currents for pools of all kinds. Together, they expanded the definition of what a swim spa could be.

Their presence also nudged acrylic spa makers to take the category more seriously — improving water flows, pursuing athlete endorsements and embracing fitness and therapy as central selling points.

By the time Master Spas put Michael Phelps in front of its swim spas in 2009, consumers already had a mental model for what these machines could do. SwimEx and Endless Pools had spent two decades building it.

Portable acrylic swim spas eventually became the mainstream product, but the swim machines gave the category its backbone.